Typical listing from a local phone book’s white pages

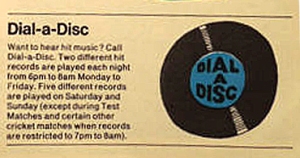

Dial-a-Disc was a music service run by the (then) General Post Office (GPO) where, by dialing 16 or 160 on your telephone, you could hear the latest hit records played down the phone line.

So how did it all come about?

The GPO were already running a number of useful dial-up information services, such as the Speaking Clock, the Weather Forecast and live Test Match Cricket Score Services, but the latter was only in use during the cricket season from May to August, whereupon it laid dormant for the rest of the year. So it was decided that an experimental music service should be run during the non-cricket months to make more use of the highly expensive Test Match Service equipment.

Dial-a-Disc was trialed first in Leeds, springing to life at 6 pm on the 7th July 1966. It ran for just under a month, before being hailed as an outstanding success! The service was started again on the 8th December 1966, again only in the Leeds area, but it was rolled out to the rest of the country gradually over a four year period. On-demand music streaming had arrived. But Hi-Fidelity it wasn’t.

Transmitted in Mono, with the bandwidth heavily squeezed, the music was accompanied by the obligatory background crackle and static hiss generated by sending the audio down miles of copper cable. But despite its shortcomings in musical quality, it was a truly magical experience – and one that had an indefinable charm about it. For 1966 was a much simpler time – before WiFi, before streaming content, before the iPod, before iTunes, before peer-to-peer file sharing, before the Internet, before the Discman & Compact Discs (CD’s), before the Walkman – and even before Compact Cassette Tapes had become widely used domestically! At the time, Dial-a-Disc was one of the only ways of hearing the latest hits ‘on demand’, save for actually buying the records themselves!

The service ran during the ‘cheap rate’ hours from 6 pm in the evening to 6 am the following morning every weekday, and all day on Sundays. Initially only the top 7 records in the charts were played on the service, with a new record being played every day. This was soon increased to the top 8, with two records being played on Sundays. Eventually, the service expanded in its latter years to include the whole of the top 20.

So, how did it all work?

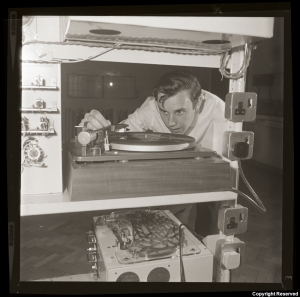

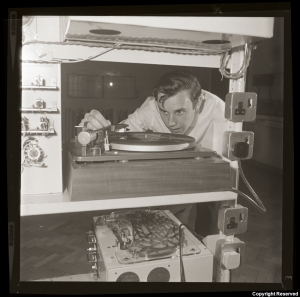

Dial-a-Disc rack (DADRACK). Photo: John Lamble. Thanks to John Chenery (www.lightstraw.co.uk) for permission to use it here.

Meet the Dial-a-Disc Rack (or DADRACK for short). It was mainly comprised of a record deck connected to a reel to reel tape recorder. Here, Post Office Technicians would record an introductory announcement, then record a hit single and finally make a tape loop of the whole recording. The tape loop was then fed into a special device called an Equipment Announcer (EA). In 1966 a new EA was designed especially for the Dial-a-Disc Service, which became known as the EA9a. A pair of EA9a’s can be seen in the above picture located below the record deck.

The EA9a was essentially a robust, high quality playback tape machine capable of holding up to 4 minutes worth of tape which played out in an endless loop. When you called Dial-a-Disc you were connected to the EA playback, more often than not in mid song depending on what part of the loop was playing at the time when your call was connected. By the mid ‘70s there were around 15 DADRACKs located in Regional Information Service Centres (RISCs) scattered around the country.

DADRACk at Judd Street Exchange, London 02/08/1967. Photo Copyright Post Office Telecoms (TCB 473_P 10075)

Dial-a-Disc was very popular, especially with the younger generation who, by and large, ran up huge phone bills across the nation. In the mid 1970s Dial-a-Disc received around 70 million calls annually, but by 1981, when the service was at its peak, it was pulling in over 200 million calls per year.

People who used Dial-a-Disc have fond memories of the quirkiness of the service. Some individuals recall that on some occasions they could sometimes hear other people talking on the line during the gaps between the end and start of the records. This appears to have been more of a problem when listening to Dial-a-Disc via public phone boxes. In some inner-city booths, youths would dial into the service specifically to chat to other local users during the quiet spots. One woman from Birmingham claimed to have met her future husband in this way!

Like all technology, unscrupulous users managed to discover ingenious ways of ‘hacking’ into the ‘system’ in order to hear the records for free. Popular methods used by phone box ‘hackers’ were the following:

Tapping out the services number rapidly on the phone handset rest buttons. Occasionally this would allow free connection to the service.

Listening to the record in installments. The GPO allowed users to listen to the first 10 seconds of the recording for free before you had to insert money into the coin box. Users would ring the service multiple times until they had managed to listen to the whole disc. Tedious, but achievable.

Finally, on earlier phone boxes that were equipped with A and B buttons* users soon discovered that they could get all their money back by hanging up just before the disc finished followed by pressing the B Button. However, the GPO eventually got wise to this trick and did some tinkering at the exchange end of the lines to prevent people from getting free listens.

There was another problem caused by the service that particularly affected small towns and villages that only had one public phone box. Clusters of youths began to hold what the press began to term ‘telephone-a-gogos’, where dozens of teens pooled their pocket money and hogged call boxes for hours on end listening and dancing to the same record over and over. This certainly happened in the North West where I lived and also in West Derbyshire, although it is unclear if this craze was a nationwide phenomenon.

My ‘love affair’ with Dial-a-Disc occurred during the summer of 1979, where I would often dial in to hear the latest sounds. However, the first quarterly bill brought my happy ‘affair’ to an abrupt end. I did attempt to call from a Phone box on one occasion, but a bunch of local yobs ran round the box with a roll of masking tape and sealed me in. Luckily, a passer-by spotted me and managed to get me out.

It was sometime during that same year that a good friend of mine found himself walking home from a party in the wee small hours in an advanced state of alcoholic intoxication. Cold and lost, he found a call box in the middle of nowhere and stepped inside in an attempt to get warm. After a few minutes he decided that he wanted to listen to some music and so put all his loose change in the coin slot and called Dial-a-Disc. With the phone cradled against his ear, he soon fell asleep to the sounds of Gloria Gaynor’s ‘I will survive’ repeating endlessly. The next morning he awoke, slumped against the glass, phone still clutched to his ear and feeling as stiff as a board. He had no recollection of the night before and was therefore surprised to find himself inside a phone box. He put the handset back on the cradle and then noticed the long queue of angry looking people gathered outside waiting to use the phone. Not one of them had thought to open the door and wake him up. Instead, they just accepted the situation and, in typical British fashion, formed an orderly queue and began to grumble.

Dial-a-Disc spun its last record sometime in 1991, when technology such as the Sony Walkman, cassette tapes and portable FM radios surpassed the service’s usefulness and musical quality. But for 25 glorious years Dial-a-Disc was a tantalising glimpse into the future possibilities of on-demand music distribution.

Here is a demonstration by a telephone enthusiast of a demo telephone exchange where, amongst other things he gives us a feel of what it was like to call and listen to the Dial-a-Disc service:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hUGsRoebaVM

———————————————————————————-

*You pushed Button A to connect your call once the person you dialled had answered their phone. When your call had ended you could push Button B to retrieve any unused coins.

———————————————————————————–

Many thanks to John Chenery, for providing me with essential information about the Dial-a-Disc service and for kindly allowing me to use some of his photographs. For more detailed information about Dial-a-Disc and other ‘obsolete technologies’ please visit John’s excellent website: http://www.lightstraw.co.uk/